|

What is it that clowns do with their legs, that’s different to what actors or dancers do? Can you spot a clown performer just by looking at their lower body? Two legs good The bipedal nature of adult humans is one of the most fundamental features in our sense of self. Walking on two legs sets us apart from animals, it lifts our heads up towards the heavens and frees our hands to hold and make things, to embrace and to fight. The idea of being upright is tied to ideas of being dignified, respectable, an upstanding citizen. It’s also, seen dispassionately, pretty silly. Bipedal creatures are top heavy, and slower moving on our two legs than even pretty tiny quadrupeds (Buckley, 2013). We have to use huge portions of our brain power simply to stop ourselves from falling over, it takes us over a year from birth to be able to walk, and several years more to master the contralateral arm swinging that allows us to walk and run with some degree of efficiency (Lewsey, 2018). Perhaps it’s this combination of dignity and absurdity that makes standing and walking upright, and the legs that we use to do that, fertile ground for comedy. This is a core idea in physical comedy performer Jos Houben’s acclaimed solo show The Art of Laughter (Houben, 2007). Houben posits that the moment we lose or subvert our upright posture, is the moment that we become ridiculous (watch here). Clown shoes and baggy trousers This train of thought around the way clowns use their legs originated in a conversation during Jon Davison’s Clown Studies course with The London Clown School (Davison, 2020). We were looking at clown costume through the ages, and I started to notice a common thread throughout the images and video clips; clown costumes that highlight the legs and feet. e to edit.

It’s a look with a lot packed in; it’s clearly feminine and reveals the performer’s body, but it’s rendered pretty and childishly innocent, rather than sexual, by its historical connotations. It also places the performance within the visual context of circus, with all its connotations of enjoyment and entertainment, rather than contemporary dance, which can be seen as elite, difficult and highbrow.

Rebellious dancing legs A possible answer to the question of what clowns do with their legs, as opposed to dancers or actors, may lie in the connectedness of the body as a whole. In Western performance dance, there is a general principle of harmony, of the body moving as one fluid shape, emphasising through line from limbs to torso and out again. Rudolf Laban has much to say on the subject of harmony, imagining the human body existing and moving within perfect invisible mathematical shapes (Newlove and Dalby, 2004) . In classical ballet, this sense of line and extension is at its zenith, with dancers spending years training for perfection of through-line, particularly in arabasque positions. Actors too often seek a sense of connectedness and harmony in their movement. There are many anecdotal examples of actors building a character from the shoes up, Alexander Skarsgård was interviewed by The Guardian on the subject recently (Skarsgård and Harper, 2019). Others find a character’s walk as a way into a role. I do a lot of work with actors on this as a movement director: creating a consistent and cohesive physicality helps define a character onstage, particularly when the actor is playing multiple roles. And for the most part, the limbs and torso all work together to paint that picture. Clowns and comedy performers seem to have a more fractious relationship with their legs. There’s often a sense of disconnect, as if the legs have a mind of their own or are being controlled by some external force. There’s perhaps an echo here of the innocent amazement that a tiny baby has, watching her own arms and legs flail around, unaware that she’s responsible for them. This disconnection is particularly apparent when we look at eccentric dance in its early 20th century heyday and beyond; from Little Titch’s big boots, through Wilson, Keppel and Betty’s bowler-hatted Egyptian sand dancers, and Groucho Marx’s ubiquitous leg-hitch move, the legs are doing one thing while the face is telling us something else. According to Davison (2020), veteran eccentric dancer and teacher Barry Grantham describes this phenomenon as the performer having eccentric legs while acting with the face and torso. The most extraordinary of the eccentric dancers was surely Josephine Baker (1906 - 1975) whose long-limbed and articulate body dancing in perfect disconnection with itself made her appear as if she had a brain in each limb, like an octopus. She also walked a fascinating line between the comic and the sexy- her most iconic dance was performed in a tutu of bananas and not much else (watch here). Her goofy facial expressions with crossed eyes and puffed out cheeks seemed to undercut the showgirl costuming and context of her performances, giving a sense (whether constructed or not) that she was dancing for her own enjoyment rather than the titillation of her audience. This somehow seems much more anarchic and empowered than many of the contemporary music stars whose acts follow in Baker’s wake; however magnificent Beyonce might be, she’s never to my knowledge blown raspberries at her audience! A classic film example is Ray Bolger’s loose-limbed and off-balance performance as the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz (Fleming, 1939). His extraordinary dance sequence to the song If I Only had a Brain was cut from the cinema release but came to light some decades later (watch here). As well as some gloriously daft in-camera effects and wirework, it features Bolger sliding into out of box splits as if completely boneless and weightless, and performing high-leaping barrel turns and landing on the sides of his feet, which appear only loosely connected to his ankles. Throughout all this virtuoso athleticism, his face retains an expression of cheerful confusion, as if his body were being puppeteered from the outside, rather than controlled by his actual human brain. Moving beyond the music hall and of the early days of cinema, and still we see dancers in popular culture forms doing weird stuff with their legs. Look Krumping or Clowning, the hip hop dance styles pioneered by Tommy the Clown (Thomas Johnson), and there yet again we see the same unruly and disconnected legs (watch here). The styles, much like Bolger’s scarecrow, play with weight, gravity and optical illusion, and again give the feeling that the dancers’ legs are being externally controlled, or possibly have a mind of their own. If as Paul Bouissac’s semiotic analysis suggests, the clown is often out of step with social and cultural norms, operating in the realms of transgression (Bouissac, 2015), what more fundamental expression of this idea could there be than the sense of being out of step with your own body? There’s a sense of anarchy in these rebellious legs, prodding at the taboo of out-of-controlness that we see and fear in drunkenness or madness, for example. Legs, or rather the body parts between and atop them, also hint at the more obvious taboos of sex and excretion, two well-worn but ever-popular sources of comedy material. Funny feet One of the clowns featured in Bouissac’s book is Portuguese circus performer César Dias, a fourth-generation circus performer whose act builds on long-established traditions. One of his most popular entrees is as a Vegas-style lounge singer performing the song My Way (watch here). Dias’s clown persona is visually pared back; he doesn’t perform in a red nose; in fact the only piece of clown ‘wrongness’ in his costume for this number is his too-short trousers. Through the course of the act, as Dias struggles with the microphone and stand, his trousers drop, revealing red satin heart-covered boxer shorts and sock suspenders. In the rearranging of clothing that ensues, the bottom of his jacket is left poking out of his flies, and if that wasn’t quite phallic enough, he then discovers that the microphone is also down his trousers. He performs the remainder of the song with the mic cable threaded through his crotch, adding injury to insult in true clown fashion as he walks too far from where the cable is plugged in and appears to cheese-wire his testicles. The genital connotations of this part of the act are clear, but in fact only Dias’s legs are ever bared; the nakedness of this usually clothed body part and the suggestive shape of the microphone, are enough to bring the taboo to mind without risking censure from a family audience. It’s interesting to note that despite Dias being conventionally attractive, there’s no sense that the element of bared flesh in this act is designed to titillate. Exposed men’s legs, the act prompts us to understand, are funny, not sexy. So what of exposed women’s legs? Clown comedian Julia Masli’s award-winning 2019 show Legs (with the Duncan Brothers) is a surreal meditation on the body part. In one section Masli makes characters out of her legs with sunglasses and drawn-on mouths, pulls a condom over one leg (which of course snaps), bangs her knees together suggestively, and then enacts giving birth to a doll’s leg. Masli seems to acknowledge the cultural expectation that her long, bare, female legs will have sexual connotations; there are wolf whistles from the audience when she first enters, wearing a fur coat and short shorts; and this section both acknowledges and subverts that expectation by suggesting a sexual act but with wonderful grotesque silliness. Masli’s more recent video collaboration (watch here) with Scandinavian clown Viggo Venn pays tribute to the joy and health benefits of squatting (Masli and Venn, 2020). Clearly an hour-long show wasn’t enough to fully cover the comic possibilities of legs. Sometimes however the joy that clowns find is in hiding or disguising rather than exposing their legs. In clown superstar Slava Polunin’s international hit production Snowshow, the central Yellow Clown’s costume is soft, billowing, and features an extremely dropped crotch. This gives the character a cartoon-like silhouette and allows Polunin and the others who have since inherited the role to create physical optical illusions. In an understated dance number to the sentimental song Blue Canary (watch here) the Yellow Clown drops into a deep squat (Julia Masli would approve) to waddle in time with the two taller Green Clowns who flank him, and performs stiff jumps where his legs appear to be pulled into his body on elastic. Even when hidden here, it’s the clown’s legs providing the visual surprise that appears to catch the unsuspecting clown out, and that’s what triggers the audience’s laugh. So What?

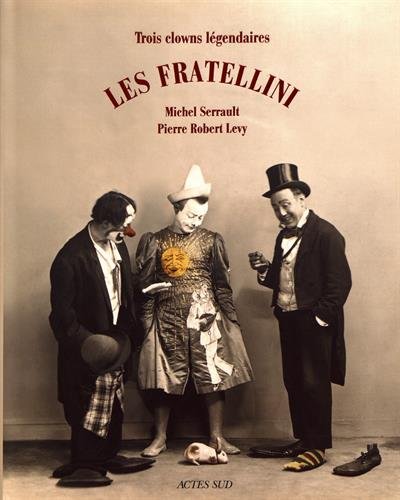

From this collection of evidence, we can argue that perhaps clowns do have an unusual relationship with their legs, and that it’s part of what makes an audience laugh. The laugh could come from the surprise of a visual illusion when a performer’s legs seem to operate of their own accord or outside the usual laws of gravity, or it could come from the boundaries of the taboo, or the subverting of a sexualised male gaze. Perhaps though there’s just something fundamentally absurd about legs, and our insistence as a species on balancing precariously on just two of them, while declaring our own sublime dignity and intellectual supremacy. References and Bibliography Bouissac, P. (2015) The Semiotics of Clowns and Clowning: Rituals of Transgression and the Theory of Laughter. London: Bloomsbury. Buckley, C.E. (2013) ‘Speed is Relative (Human and Animal Running Speeds): Are you a Cheetah, a Chicken, or a Snail?’, Faculty and Staff Publications- Milner Library, Illinois State University, 46. Cesar Dias MY WAY- comedy act [YouTube] (2017). Switzerland. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZmGBQY1Np-Y. Davison, J. (2020) ‘Clown Studies Course: History, Theory and Analysis of Clown’. Online, September. Fleming, V. (1939) The Wizard of Oz [Film]. MGM. Fleming, V. and Haley, J. (1985) Wizard of Oz Outtake, from ‘That’s Dancing!’ [YouTube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7qFIuy_7Z0g. Hall, J. (2017) Little Titch- Big Boot Dance (1900) [YouTube]. J R H Films. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFB4oHajwGw. Houben, J. (2007) ‘The Art of Laughter’. Battersea Arts Centre, London. Josephine Baker’s Banana Dance [YouTube] (2008). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wmw5eGh888Y. La verticalité par Jos Houben, L’Art du Rire - La Scala Paris [YouTube] (2020). Available at: https://youtu.be/y4cp6g_gFCk. Lewsey, J. (2018) ‘Your Child’s Walking Timeline’, babycentre.co.uk. Masli, J. and Venn, V. (2020) Julia Masli and Viggo Venn: Masters of Squat [YouTube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKLJXOfJmr4&t=6s. Newlove, J. and Dalby, J. (2004) Laban for All. London: Nick Hern Books. Skarsgård, A. and Harper, L. (2019) ‘Alexander Skarsgård: “I spend hours thinking: ‘What kind of shoes would this guy wear?’”’, The Guardian, 1 October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2019/oct/01/alexander-skarsgard-i-spend-hours-thinking-what-kind-of-shoes-would-this-guy-wear (Accessed: 12 January 2022). Slava’s Snowshow Théâtre Monfort Paris [YouTube] (2012). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Oc72-gVtOg. What is Clown Walking? [YouTube] (2020). OfficialTsquadTV. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zT8_yoYirNw. Figures: 1: Joey Grimaldi as Clown, from http://www.historyofcircus.com/circus-origin/joseph-grimaldi/ 2: Lizzie Muncey and Maisie Whitehead in WinterWalker’s The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, 2016. Photo by Tim Cross, ©WinterWalker 3: Book Cover of Les Fratellini, Trois clowns légendaires by Michel Serrault and Pierre-Robert Levy, from https://www.amazon.co.uk/Fratellini-Trois-clowns-légendaires/dp/2742713638

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The BlogThoughts, notes, rants and questions, written from within the clowndance research process.

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed